Of all the things I love about The Wheel of Time, it wasn’t until my most recent reread of the series that I truly noticed the striking geology of Robert Jordan’s world, and how it’s incorporated into the storytelling. I first read the books when I was in middle school, but I have a different outlook now, twelve years later and in the middle of completing a Ph.D. in geology. An eye trained by observing faults and erosion, so accustomed to reading the clues and histories hidden in the features of the Earth, can’t help but conceive a new appreciation for how Jordan constructed his fictional setting, weaving so much information, thought, and nuance into every detail.

Below, I’ll discuss three of the key features of the place we fans call Randland, and how they deepen our understanding of the world and its history from a geological perspective…

The Aiel Waste

The Three-fold Land is one of my favorite settings in The Wheel of Time. It is an arid, harsh desert bordered by the Dragonwall mountains to the West and mysterious Shara in the East. The lack of water has clearly impacted the culture of the people who manage to survive here–the scarcity is reflected in the Aiel’s reverence for water and their fear of it.

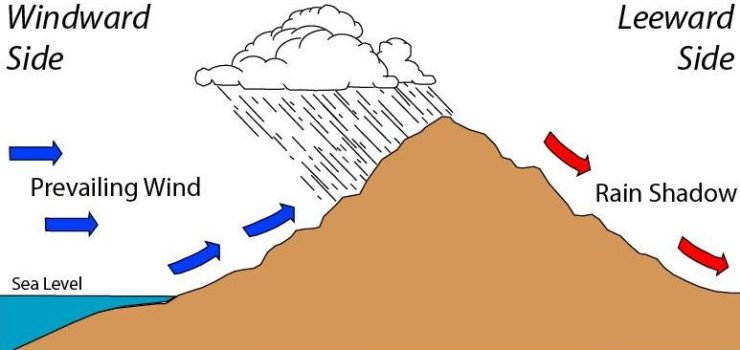

Why do they lack water? Geographically speaking, the Aiel Waste is located in a rain shadow. This occurs when a mountain range (the Dragonwall, in this case) blocks moist air and reduces the rain on its leeward side (opposite to the direction of the wind). Some examples of real-world rain shadows include the Sahara Desert, which is blocked from the water-laden gusts from the Mediterranean by the Atlas Mountains to the north, and the Tibetan Plateau, which is shadowed by the Himalayan Mountains. The Aiel Waste is blocked on multiple sides by mountain ranges, much like the Sahara, and this may increase the effects and further limit the water reaching the Three-fold Land.

The Dragonwall mountains are more than large enough to cause a large rain shadow which is affected by both the height and length of the chain. Scientists who study climate modeling recently created a model of the world of The Wheel of Time, set 18,000 years from the present day. You can see the wind cross the Dragonwall and sweep into the Waste here.

The Dragonwall stretches from the Mountains of Dhoom to the Sea of Storms, effectively blocking off a huge area. Rand describes the mountains as “the tallest thrust well above clouds that mocked the Waste with promises of rain that had never come.…men who had tried to scale these heights turned back, overcome with fear and unable to breathe” (The Fires of Heaven, Chp. 20). Notably the mountains are tall enough for the oxygen levels in the air to drop due to low pressure, likely over 14,000 feet, at which point altitude sickness becomes more prominent. Thus, the high mountains block the Waste from getting any rain and the water that does exist there is mostly available in deep aquifers.

However, we learn that this wasn’t always the case, and that the Three-fold Land might have once been underwater. When crossing Jangai Pass, Rand notes a building jutting out from the mountain:

He could have sworn it was the remnants of shattered buildings, shining gray against the darker mountain, and stranger still, what appeared to be a dock of the same material, as for ships, slanting drunkenly down the mountain. If he was not imagining it, that had to date from before the Breaking. The face of the world had changed utterly in those years. This could well have been an ocean’s floor, before. (The Fires of Heaven, Chp. 20)

Here, Jordan again shows that the legacy of the Breaking is always present—surrounding the characters on all sides, written into the very landscape. Which brings us to…

The Breaking

One of the most impactful descriptions of the Breaking comes from Loial : “Ogier were scattered like every other people, and they could not find any of the stedding again. Everything was moved, everything changed. Mountains, rivers, even the seas” (TGH, Chp. 35).

The Breaking was a disaster of geologic proportions where landmarks were made meaningless, features changing so quickly that maps were made irrelevant in days or even hours. Nothing in geology compares to the speed of the Breaking–change on that immense scale does take place on Earth, but at a much, much slower pace.

The comparison really illustrates the scale of the horror, destruction, and madness of the Breaking and underscores the power of the Aes Sedai in the Age of Legends. Today continents are arrayed on plates which move across the Earth’s surface, collide, split apart, and sink under one another, creating new mountains and seas—but incredibly slowly. This process is called plate tectonics. The fastest rate of plate motion is only 15 cm/yr (6 in/yr), which is about as fast as hair grows, and most plate motion is significantly slower. I estimate that the motion of plates during the Breaking was probably millions of times faster. Mountains rose up and were toppled multiple times during the approximately 300 years of the Breaking–makes me sweaty just thinking about it…

At one point Elder Haman, an ogier elder, tells Rand that during the Breaking, “[d]ry land became sea and sea dry land, but the land folded as well. Sometimes what was far apart became close together, and what was close, far” (Lord of Chaos, Chp. 20). Though we normally think of rocks as solid, stiff things, folding of rocks can occur with enough time and pressure. Mountain ranges can be formed from rocks folding and faulting on huge scales.

Over the course of Earth’s history, the creation of mountains, rivers, and seas has occurred countless times, moving in constant opening and closing cycles. If you could go back 400 million years ago, much like the Ogier, you would not be able to find your hometown as it currently exists, much less point to where your country should be. You can use this map to explore what the world looked like millions of years ago and look at where the place you call home might have been located back then. The Earth has experienced many past ages in which the paradigms of life and climate were much different from anything in our current reality. There are seas opening and closing right now (the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, respectively), just as there are mountains being built (the Himalayas) and mountains being destroyed (the Appalachians). It is just happening very, very slowly. No need to be hasty.

One of the lessons that both Robert Jordan and my study of geology have instilled in me is that the Wheel keeps on turning and ages come and pass and come again. Just as 400 million years ago most of North America was completely underwater, it will be again—the progress of plate tectonics is just as relentless as the One Power. In the cosmology of The Wheel of Time, the True Source drives the turning of the Wheel and the progression of time. In a sense, the One Power can be seen as the same force that drives plate tectonics, making and remaking our world.

The Formation of Dragonmount

A couple months ago, I attended a conference about the impact of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Following the latest research on impact craters is one of my hobbies, along with my love of fantasy–so you can imagine that I take every chance I get to combine the two! While rereading The Eye of the World, I was struck with how much the section of the Prologue describing the formation of Dragonmount relates to impact craters. Here’s the text as written:

From the heavens it came, blazed through Lews Therin Telamon, bored into the bowels of the earth. Stone turned to vapor at its touch. The earth thrashed and quivered like a living thing in agony. Only a heartbeat did the shining bar exist, connecting ground and sky, but even after it vanished the earth yet heaved like the sea in a storm. Molten rock fountained five hundred feet into the air, and the groaning ground rose, thrusting the burning spray ever upward, ever higher. From north and south, from east and west, the wind howled in, snapping trees like twigs, shrieking and blowing as if to aid the growing mountain ever skyward.

(The Eye of the World, Prologue)

Buy the Book

The Wheel of Time Companion

From a geological perspective, that’s basically what happened when the asteroid hit the Yucatán Peninsula 65 million years ago. Following that kind of impact, the immense friction and kinetic energy immediately vaporizes everything in range, leaving a crater and transmitting huge amounts of energy into the earth, which causes an earthquake. Just like dropping water into a pool, after the initial impact, the surface then rebounds and fountains upward.

In the case of the crater in the Yucatán, it actually collapsed further after impact, leaving a mostly flat scar instead of a traditional bowl-like crater. In the books, when Lews Therin Telamon draws too much of the One Power, the surface of the earth continues to rise into the volcano Dragonmount. Generally, volcanoes form when rock melts due to tectonics; however, rock can also be melted by impacts. Recent research from drilling into the crater in the Yucatan indicates that magma was present under the crater for thousands (if not a million) years after the asteroid hit the earth and could in theory have caused a volcano to erupt above it. Now, I suppose RJ could have been inspired by atomic bombs rather than natural catastrophes in his description of this event, but why not let a girl geologist dream!?

***

Geology has always been about storytelling: It is a skill set through which, by looking at the world around us, we can reconstruct its history going back millions or billions of years. We all live in a world where the laws of geology continue to shape the planet, just as they have always done. We observe erosion, uplift, and climate as part of our daily lives and are able to intuit how it all works. And when something in a fictional world doesn’t feel right, readers will tend to notice it, such as the wacky distances in Randland. The consideration of the physical world around the characters is in many cases just as important as the intricately constructed cultures, and Robert Jordan’s careful inclusion of various geologic features and processes is another example of the thoughtfulness and breadth of his extraordinary worldbuilding. The physical world can work as a powerful storyteller.

In the comments below, I hope you’ll point out other geological details in the books, and moments where Jordan’s worldbuilding seems to draw upon science for inspiration. And please let me know if you have any geology-related questions–I’d be happy to calculate the speed and pressure of the lava from Androl’s LavaGates in A Memory of Light, for example, if anyone wants to know!

Update: re: Androl’s LavaGates—ask and ye shall receive! First, let’s review what the books says:

Something exploded out of the gateway, as if pushed by an incredible force. A column of lava a hundred feet in diameter, blazing hot. The column broke apart as the lava crashed down, splashing to the battlefield, gushing forward in a river. The Asha’man outside the circle used weaves of Air to keep it from splashing back on the circle and to shepherd it in the right direction.

The river of fire washed through the foremost Trolloc ranks, consuming them, destroying hundreds in an eyeblink.

To calculate the speed of the lava we need three things: first, the pressure of the magma under Dragonmount, then the pressure where Androl makes the gates, and lastly the density of the lava.

To figure out the pressure, we will calculate the lithostatic pressure, the pressure of the rock on top of the magma chamber. For a magma chamber volcano at 10km (6 mi) depth pressure is about 30 MPa. But let’s put that in the unit of Torr, just because… So it’s 225,000 Torr.

At the other end of the gateway, the pressure is just the air around it, atmospheric pressure which is 760 Torr. It’s a big difference.

Finally, the density is trickier. Different types of magma have very different densities and different viscosities, which you can think of as degrees of splashy-ness. Honey is not very splashy; it’s thick and gooey, so it has a high viscosity. Water is splashy and has a low viscosity. But here, it’s described in the paragraph as quite splashy so I will assume it has density similar to other less viscous lavas such as basalt, and thus we’ll just use the density of basalt which is 3000 kg/m^3. [Bonus fact: assuming it’s a basalt, the temperature would be about about 1200 ℃ or 2200 ℉.]

We can use the two pressures and plug them into the Bernoulli equation to get the speed of the lava rushing through the LavaGate:

![]()

This neglects potential energy. I assume that since the gateway makes a fold in the pattern the two points are spatially the same for its duration. We put in the pressure of the magma, the pressure of the air, and the density, then solve for the velocity, v. It’s about 140 m/s or 310 mph—faster than the top speed of a peregrine falcon!

Allison Kubo Hutchison is a Ph.D. candidate studying geophysics. She listens to about 100 hours of fantasy/scifi audiobooks a month.